“South Korea and the Nuclear Puzzle: Is

Self-Nuclear Armament the Answer?”

“Of course, if the problem becomes more serious, we may deploy tactical nuclear weapons here in Korea, or we may have our own nuclear weapons.”

On January 11,

President Yoon Seok-Yeol’s remarks reignited the debate about the nuclear

armament of Korea. Although the Washington Declaration has strengthened South

Korea’s ability to protect itself, its evaluation was divided between experts

and the general public. For experts, it was hailed as the best agreement,

yet the public criticized the concession as a hurdle in the way of

self-nuclear armament. It is evident that aspirations for self-nuclear

armament remain in Korean society. Thus, in this column, The Sogang Herald

will examine the Washington Declaration, the history and meaning of

self-nuclear armament, and the necessity and possibility of self-nuclear

armament through a multi-faceted analysis.

What is

Self-Nuclear Armament?

Self-nuclear

armament refers to acquiring the ability to deploy nuclear weapons without

depending on a foreign nation such as the United States of America. South Korea

has made several attempts at nuclear armament in the past. Under the Park

Chung-hee administration, the country established the Arms Development

Committee and the Defense Science Research Institute. South Korea acquired

nuclear-reprocessing technology from France, imported heavy water reactors from

Canada, and obtained missile technology from the United States. With the

fundamental requirement of nuclear development met, only the development phase

was left for South Korea to achieve nuclear armament. However, the fear of the US

pressure and sanctions led to the termination of nuclear development in 1976.

During the new military administration led by Chun Doo-hwan, a nuclear

development plan utilizing plutonium, a radioactive material used to produce

nuclear weapons, was promoted in 1982, extracting a significant amount of

plutonium. Yet when the United States government became aware of these

activities, Chun Doo-hwan was forced to abandon the nuclear program in

1983.

Even after the

civilian government took office, South Korea clandestinely conducted

experiments related to uranium conversion, enrichment, and plutonium separation

until the 21st century. However, these activities were

halted once again due to special inspections by the International Atomic Energy

Agency. Subsequently, there were no significant developments until the Yoon

Seok-yeol administration, which sparked heated debates on self-nuclear armament

until official remarks regarding the conditional self-development of nuclear

weapons were made. The discussions continued until the Washington Declaration

was presented to the public.

This Washington

Declaration was also one of America’s acts for quelling Korea’s aspirations for

nuclear armament. The Washington Declaration gives South Korea a central role

in the strategic planning for the use of nuclear weapons in any conflict with

North Korea. In return, South Korea agreed not to pursue its own nuclear

arsenal.

©Office

of the President of the Republic of Korea

©Office

of the President of the Republic of Korea

Views on the

Washington Declaration are divided, with some reacting positively to a more

conventional weapons arrangement and more influence on America’s nuclear

weapons. However, others criticize the move as it completely abandons the

option to develop and possess Korea’s own nuclear arsenal. One expert argues

that the US-ROK Nuclear Consultative Group is the best choice for the United

States, concerned about the domino effect leading to nuclear proliferation, and

the Korean government, seeking to secure extended deterrence. He emphasizes the

importance of constantly exerting Korea’s influence on America’s nuclear weapon

control by implementing the NCG.

On the other hand,

experts on the other side argue that the Washington Declaration is the complete

waving of the right to withdraw from the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty(NPT).

Also, they are suspicious about the faithful implementation of the declaration

under a radical right-wing government, citing the example of President Trump.

Furthermore, they point out that the Korean government fails to revise the

Korea-US Nuclear Agreement, which imposes stringent conditions on spent nuclear

fuel reprocessing and uranium enrichment compared to the US-Japan Nuclear

Agreement. So far, we’ve looked at the self-nuclear armament itself and Korea’s

failed attempts. At this point, this column intends to pose a question. “Do the

Koreans really think that the self-nuclear armament is required?”

“Does the Korean

Public Want a Nuclear Arsenal?”

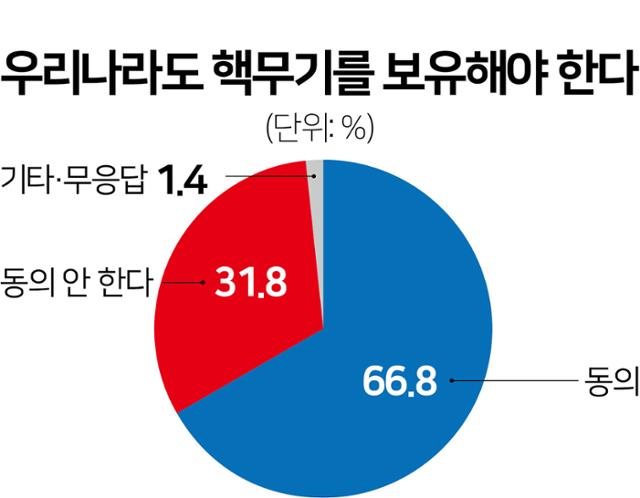

In some surveys,

it seems that there are aspirations for self-nuclear armament among Koreans.

According to Gallup Korea surveys conducted in the 2010s, approximately 50-60%

of the public expressed support for nuclear development. More than half of the

population holds a favorable view of the concept of nuclear armament. According

to the Hankook Ilbo/Hankook Research New Year’s opinion poll, 66.8% of

respondents (34.0% strongly agree, 32.8% generally agree) agreed with the claim

that South Korea should possess nuclear weapons. In contrast, only 31.8%

disagreed with this claim. Across different ideological affiliations, more than

half of liberals (54.4%), moderates (70.7%), and conservatives (69.5%) agreed

with the idea of South Korea possessing nuclear weapons. When asked about the

United States' stance in the event of a military clash between the two Koreas,

only 36.7% of respondents believed that the United States would unconditionally

support South Korea. A more significant portion (53.6%) thought the United

States may or may not intervene based on self-interests. Some respondents even

suggested that the United States might not intervene due to concerns about

burden-sharing (4.1%). Despite the 70-year history of the ROK-US alliance,

there is an underlying consciousness that blind trust and reliance on the

United States may not be advisable in emergency situations.

©Hankookilbo

However, the 2023 Asan Institute for Policy Studies survey revealed some important points. When the possibility of sanctions was not mentioned, 64.3% agreed, and 33.3% disagreed with self-nuclear armament. But, when the possibility of sanctions was introduced, the percentage of agreement decreased to 54.7%—simply mentioning the possibility of sanctions led to a decrease of about 10% in support. It can be inferred that the lack of accurate information about international sanctions and potential risks might contribute to the public’s support of the self-nuclear armament process. Also, from a political psychology paper that focused on the relationship between Korean’s opinion about self-nuclear armament and knowledge about the consequences that Korea will face if the self-nuclear armament happens, 58% of participants who support the self-nuclear armament changed their decision after getting information about opposing arguments such as international sanctions and economic disadvantages. Also, 32% of participants who opposed the self-nuclear armament changed their minds after getting information about consenting arguments. All these facts mean that Koreans require more information about self-nuclear armament and its consequences for making their true decisions. Therefore, it seems crucial to convey detailed information about the necessity, feasibility, and possible outcomes of pursuing self-nuclear armament.

Is Self-Nuclear

Armament Necessary?

The need for

self-nuclear armament is underscored in a country like South Korea, where a

hostile nation, North Korea, is aiming its nuclear arsenal at it. In September

2022, North Korea legalized “nuclear weapons legislation,” explicitly stating

the possibility of preemptive nuclear strikes. Until now, North Korea has

maintained an attitude of possessing nuclear weapons for self-defense, but this

legal provision opens up the possibility of preemptive strikes. Nuclear weapons

give a nation overwhelming asymmetric power, which traditional conventional

weapons find difficult to counter. Therefore, the concept of “mutually assured

destruction” is crucial for peace. MAD refers to a state where the annihilation

of both the aggressor and the defender is certain. Therefore, no entity will

preemptively strike a nation with a nuclear weapon. If one side launches a

nuclear attack, the other side will also respond with their nuclear weapons,

resulting in the complete destruction of both parties without gaining any

advantage. In this regard, South Korea is highly vulnerable to a nuclear attack

from North Korea. Relying solely on conventional weapons is almost impossible

to counter nuclear threats.

©KCNA

Some might think

that America will act as a nuclear umbrella for South Korea. However, distrust

towards the United States is hard to overcome for South Koreans. Trump’s America

First policy, popularly known as MAGA, shattered the image of the United

States as the world’s sole superpower that had been established since becoming

the only leading power in 1991 after the collapse of the Soviet Union. During

the four years of the Trump era, the United States emphasized its

prioritization of national interests over the interests of allies and did not

hesitate to show this stance. Even during the Biden era, the United States

refrained from direct intervention to avoid a military conflict with Russia.

This demonstrated how fragile the US commitment to defending South Korea is in

the face of asymmetric power like nuclear weapons. In these circumstances,

doubts and suspicions about whether the United States would assist Korea, even

at the risk of a preemptive strike, are dominating Korean society.

Furthermore,

possessing a nuclear weapon gives a nation unparallel diplomatic and political

leverage over the other. In fact, during the Park Chung-hee administration, South

Korea gained access to advanced nuclear power technology by abandoning nuclear

weapons development. Even without developing nuclear weapons, there are

considerable benefits to be gained from utilizing this situation. With the

benefit outweighing the risk, the debate over nuclear weapons development

continues.

Is Self-Nuclear

Armament Possible?

Regardless of the

necessity of nuclear weapons development, the question remains regarding the

feasibility of nuclear development. Technically, it is possible. South Korea

already possesses reprocessing and enrichment technologies that can be used to

develop a nuclear weapon and can produce a prototype with a yield of 20

kilotons (kt) within six months if there is a political decision. While it is

possible, it is politically and economically catastrophic. First, the United

States will never consent to South Korea possessing its own nuclear arsenal,

fearing South Korea will create a Domino effect leading to nuclear

proliferation, which is evident based on its past actions against the nuclear

development program of South Korea, Iran, North Korea, South Africa, Israel,

and Libya.

So, what if South

Korea were to develop nuclear weapons without the consent of the United States

and endure international sanctions? In such a case, international sanctions

would be inevitable. With crippling sanctions from the international community,

the Korean economy would likely be paralyzed as it is an export-oriented

nation. With an economy mainly based on exporting finished goods such as

semiconductors and cargo ships, which heavily depend on imported goods as their

raw material, economic sanctions will destabilize the nation’s industrial

foundation, leading to economic collapse.

Some might suggest

Korea follows the path of Pakistan and India, which successfully developed

nuclear weapons despite enduring international sanctions. However, Pakistan and

India were in a different situation compared to South Korea. There are three

key factors that contribute to this distinction.

First, India and

Pakistan had a low economic dependency on the United States. Until the late

1980s, when they were actively pursuing nuclear development, both economies

were composed of primary industries, such as agriculture, that enabled them to

withstand US economic sanctions without suffering significant blows. In the

late 1970s, when the sanctions were imposed, India’s import/export ratio to GDP

was just over 10%. Pakistan also had a lower export-import ratio and a higher

dependence on agriculture. Therefore, the limitations of US-led sanctions were

evident. Additionally, there is no guarantee that South Korea could swiftly

recover from such sanctions, as India and Pakistan did in the past.

Secondly, South

Korea is a democratic country. If its export-driven economy were to be hit by

sanctions, public opinion domestically would deteriorate, potentially leading

to a change in government in the next election. A newly elected government

would likely abandon pursuing nuclear weapons and return to the NPT based on economic

considerations. Consequently, it can be concluded that it is highly improbable

that Korea will develop a nuclear weapon.

A risky Gambit

Nuclear armament

seems necessary in the face of the North Korean nuclear threat and weak

commitment from the U.S. However, factors such as condemnation from the

international community and possible economic sanctions are too significant a

risk to pursue Korea’s nuclear program. Therefore, South Korea’s self-nuclear

armament is a risky gambit while a safer, more diplomatic resolution

still exists.

By Park Jeonghyun (cub reporter)

j010704@sogang.ac.kr