The Seoul Metropolitan Subway Might Grind to a Halt

Suppose one day the Seoul Metropolitan

Subway stopped operating, with no means of resuming services. Millions of

commuters would be stranded, unable to reach their destinations. Unlikely

though it may seem, considering the system’s highly modern, advanced, and

reliable reputation worldwide, this could very well become a reality in the

near future. The truth is that Seoul Metro, the municipal-owned enterprise

responsible for providing metro services in and around the Seoul metropolitan

area, is suffering from an annual deficit of over ₩1 trillion, with an

accumulated debt of over ₩6 trillion. To put these numbers in context, Seoul

Metro is currently on the brink of going bankrupt, with overwhelming profit

losses piling up with each and every day of operation.

Responsible for transporting over seven million passengers daily, even after the breakout of COVID-19, the Seoul Metropolitan Subway is the true backbone of modern Korean society. To lose such a system on which so many heavily rely on a daily basis would bring about serious consequences to the most far-reaching character. Therefore, The Sogang Herald aims to investigate the origins and causes of Seoul Metro’s current financial state of affairs and bring attention to this urgent matter.

▲ Posters emphasising Seoul Metro’s financial situation such as the one above can be seen all around the network.

Why the Seoul Metropolitan Subway was Destined to Lose

Money

Before analysing what has caused the

situation to deteriorate to its current state, it is important to understand

that a metropolitan railway system is a massive piece of infrastructure

requiring regular, large-scale funding just to keep it in operation. Several

essential aspects in providing a functioning rail service include stations,

tracks, and most importantly, the actual vehicles that carry the passengers.

Seoul Metro recently endeavoured in renovating most of the run-down stations

along Line 2, whilst expanding its plans to a selection of stations on Line 1.

Alongside this, they have also been tasked with replacing their ageing fleet of

railcars dating back to the 1980s and 1990s. In fact, an investigation from

2020 showed that out of the total 3,551 vehicles owned by Seoul Metro, 2,535

were over 20 years old. Considering the design life of standard metro trains is

usually around 25 years, 72% of Seoul Metro’s vehicles are nearing the end of

their service life and are thus in need of replacement. The network itself is

also expanding rapidly—lines are actively being extended to cater to major

suburban residential areas such as Jinjeop on Line 4 and Hanam on Line 5,

with discussion about extending Line 6

into Namyangju-si ongoing. With all of this in mind, it becomes apparent why

Seoul Metro is currently experiencing financial hardships.

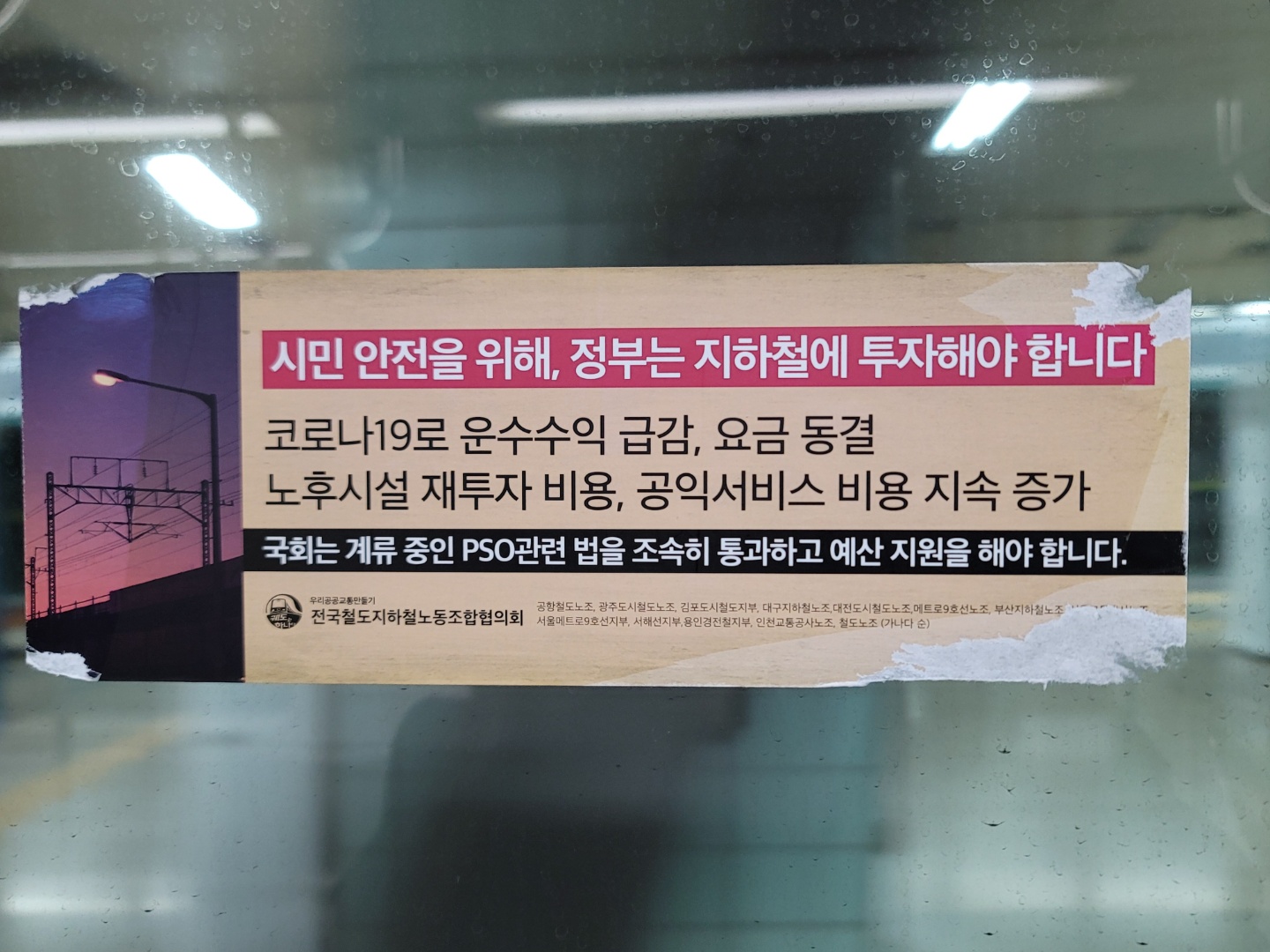

One may ask why Seoul Metro is losing so much money when it has millions of passengers paying fares. The answer can largely be boiled down to three major factors. Firstly, Seoul Metro has a unique policy that exempts senior citizens aged 65 and above from having to pay fares. The origin of this policy can be traced back to 1980 when the government decided to discount fares by 50% for seniors of ages 70 and above. The age threshold was later lowered to 65 in 1982 and, in 1984, the discount rate was increased to 100%, effectively allowing seniors to ride the metro for free. As of now, an estimated 20% of Seoul Metro passengers are non-paying seniors, a number that amounts to a total loss of over ₩800 billion in fares just in 2022.

▲ The above chart shows the estimated losses per year resulting from the senior fare exemption policy.

Secondly,

the fares that Seoul Metro is charging for its passengers are outstandingly

low, even compared to similar public transport systems around the world.

Specifically, as of 2022, Seoul Metro is charging ₩1,250 as the base fare with

an additional charge of ₩100 for every 5km from a travel distance of 10km to

50km, after which ₩100 is added every 8km. Compared with, for example, the

London Underground, which charges a base fare of £2.40—approximately ₩3,800—in

Zone 1[1]

with additional fares for those who travel in outer zones, it is clear how low

the fares charged by Seoul Metro actually are. Another example of a public

metro system would be the New York City Subway, which charges a single fee of

$2.75 regardless of the distance. This is roughly ₩3,800, once again far

exceeding what Seoul Metro charges for a trip.

Lastly, despite being in charge of large-scale infrastructure in dire need of funding, Seoul Metro is not receiving the financial support it needs from the government. This is because Seoul Metro is currently under the management of the Seoul Metropolitan Government rather than the central government of Korea. To understand the problems resulting from this, it should first be noted that the Seoul Metropolitan Subway is actually operated largely by two organisations, Seoul Metro and Korail, the state-owned national railway operator of Korea. Seoul Metro is responsible for the operation of most sections on lines 1 to 8, whilst Korail mainly provides services on longer suburban routes such as the Gyeongui-Jungang Line and the Suin-Bundang Line. Because the lines served by the two operators are integrated into one whole system, Seoul Metro and Korail are all experiencing massive losses. The only difference is that Korail, being directly owned and managed by the central government, is able to make up for a large portion of its losses through government funding–something which Seoul Metro severely lacks and desperately needs. As of now, the Seoul Metropolitan Government and the central government are refusing to provide financial support to Seoul Metro, holding each other accountable.

Previous Attempts to Save the Metro

Though Seoul Metro’s financial situation

worsened rapidly between 2020 and 2022, mostly as a direct result of a lower

ridership due to COVID-19, the company has always suffered from massive

deficits. With raising fares and receiving government funding being out of the

question, Seoul Metro had to find some way of making up for its losses, and

just like any other company, the first thing it did was drastically decrease

its workforce. Fewer and fewer staff members can be seen at stations, and

Driver Only Operation (DOO)[2]

is becoming the norm throughout the network. Less staff implies that there are

fewer employees to ensure that passengers arrive at their destinations safely

or to assist those in need.

DOO is a major

controversy as trains are traditionally operated by a minimum of two crew members,

a driver to operate the train and a guard to manage every other aspect such as

passenger boarding and announcements. Entrusting all of these responsibilities

to the driver alone would not only put too much pressure on one person, but

would also most likely impose a safety hazard, as driving a train safely

requires high levels of concentration and situational awareness, both of which

are difficult to maintain when having to carry out a multitude of jobs

simultaneously.

Another

recent endeavour of Seoul Metro is the selling of sub-station names to private

enterprises. A sub-station name is a secondary name given to a station which is

written in parentheses next to the station’s primary name. Sub-station names

were usually based on significant landmarks or major institutions which

represented the area. This is why a lot of stations on Line 2 have names of

local universities included in their names. However, Seoul Metro is now trying

to expand the sub-station name system to allow private enterprises to display

their names if they pay a large enough sum of money[3].

Though on the surface this may sound like a clever way to make up for Seoul

Metro’s losses, it brings about its own set of drawbacks.

Firstly, due to the

nature of this policy whereby anyone can submit their business’ name if they

pay enough money, companies that do not have much to do with a station—usually

because they are located a considerable distance away—are registered as the

sub-station name at times. It may be an effective way of advertising, but it

does little to aid passengers who are trying to find out where they are going,

and it also does not comply with the original purpose of a station name, which

is to inform passengers of their destination.

This leads to the second problem of this policy which is that it undermines the value of public service that Seoul Metro is obliged to provide. Several examples of paid sub-station names include Euljiro 1-ga (Hana Bank), Apgujeong (Hyundai Department Store), and Yeouido (Shinhan Investment Corporation). This clearly shows that the policy has more or less degenerated station signs into hoardings for advertising, as well as revealing how financially unstable Seoul Metro is nowadays. One thing is for certain—this should only be a temporary stopgap measure to get Seoul Metro out of the worst possible scenario and nothing more.

▲ An example of a paid sub-station name

What Can be Done?

With passenger numbers shrinking since the

outbreak of COVID-19, Seoul Metro’s financial crisis has snowballed rapidly to

a point where it is almost about to throw the company into bankruptcy. This is

an urgent matter, and something has to be done quickly. Focusing on the causes

of Seoul Metro’s current operating deficits, several options can be explored:

reforming the senior fare exemption policy, raising the fares, or persuading

the central government to take responsibility and provide the financial support

that Seoul Metro desperately needs.

Currently,

the public opinion is divided around whether to abolish the senior fare

exemption policy or to raise the fares. Fare exemption policies for the elderly

as well as low fares in general could be seen as a means of social welfare for

the country’s citizens. In this context, it would seem inevitable that

someone’s or even everyone’s welfare would be sacrificed to some extent in

order to alleviate the situation. Senior citizens claim that allowing them to

ride the metro for free is the least the country can do for them as a means of

welfare, whilst fare-paying citizens argue that raising the fares would mean a greater

burden when the cost of living is already increasing rapidly. Though both sides

have legitimate arguments, a compromise must be made. As explained above, the

senior fare exemption policy was introduced in 1984, a time when only a small

percentage of the population was older than 65. The policy was enforced by

former president and dictator Chun Doo-hwan without proper consideration and

foresight of how the population demographic would change over the coming years.

As of 2022, seniors aged 65 and above take up a whopping 17% of Seoul's entire

population, making the current fare exemption policy no longer feasible. It

might not be possible to abolish it completely, but considering the rapidly

increasing life expectancy, raising the age threshold by around five to ten

years could be a possible solution.

A

similar compromise could be made for the low fares. Whenever Seoul Metro tried

to raise its fares, it collided with fierce political objection, resulting in

the fares being frozen in place for over seven years since 2015. In a

democratic system, populism is a powerful drive, and in an attempt to gain

support for the next elections, politicians often make important decisions

based on the popular opinion rather than what actually has to be done. This is

not to say that the popular opinion is wrong, but rather, that it is easy to

overlook the self-serving nature of the public. Seoul Metro’s base fare is less

than one-third of the fares charged by other public transport systems in

similarly developed nations such as the London Underground and the NYC Subway.

Though it may seem unreasonable to triple the current fares, it cannot be

denied that it is about time they were raised by at least a marginal amount.

Of

course, all of these suggested measures are probably not enough to make up for

the massive losses Seoul Metro is experiencing each year. This is all the more

reason why the central government should step in and take responsibility. After

all, it was the central government that contributed to the current situation by

enforcing the senior fare exemption policy in the first place. A metropolitan

city administration alone cannot support nor sustain such a massive network. It

is time to put an end to the tug-of-war of responsibility. If Seoul Metro does

end up ceasing its operations, the citizens will be the ultimate victim.

It is Time to Act, and Fast

For this situation to be resolved, citizens must understand the urgency of the matter and participate in the decision-making process based on accurate, concrete facts and reasoning. Whether it is decided to alter the senior fare exemption policy, raise the fares, or have the central government invest citizens’ taxes into supporting the metro, a consensus on which a good majority can agree should first be reached. This is not a matter that can be solved within a short period, so it is paramount to be alert to and stay away from populist ideas which could easily revert the situation to its original state. The Sogang Herald hopes that readers are well aware of the current issue and urges them to take action by voicing their opinion. It is either now or nev

By Kim Tae-uck (Int’l & Social Editor)

ypyitu@sogang.ac.kr

[1] The London Underground fares are calculated on a zone-based system whereby the network is divided into 9 different zones, Zone 1 being the city centre with the rest of the zones radiating outwards.

[2] Driver Only Operation refers to a system whereby the driver alone takes responsibility for a train service without any other staff members on board.

[3] For instance, buying a sub-station name for one year costs ₩220 million for Euljiro 4-ga Station and ₩230 million for Yeoksam Station.